I recently had a meeting with a well-known Israeli startup investor. The talk somehow pivoted from my seed-seeking startup into talking about the macro view of venture capital and how it doesn’t actually make sense.

“Ninety-five percent of VCs aren’t profitable,” he said. It took me a while to understand what this really means.

I’ll clarify: Ninety-five percent of VCs aren’t actually returning enough money to justify the risk, fees and illiquidity their investors (LPs) are taking on by investing in their funds.

Who’s actually succeeding in making money?

A VC fund needs a 3x return to achieve a “venture rate of return” and be considered a good investment ($100 million fund => 3x => $300 million return). The graph below shows what percentage of VC firms accomplish this. As we can see, only the small green slice is bringing it home. The other 95 percent are juggling somewhere between breaking even and downright losing money (remember to adjust for inflation).

The graph was hard for me to take in at first. But once you run the numbers, it all makes sense. I’ll attempt to reconstruct the arguments leading to this hard-to-grasp realization of an industry so often idealized from the outside. Ready? Let’s have some fun.

If you like this article, subscribe to TechCrunch+

Use discount code TCPLUSROUNDUP to save 20% off a one- or two-year subscription

Assumptions

Before starting, let’s define what success and failure actually mean and list our assumptions:

Success = 12 percent return per year

Venture capitals get their money from limited partners, who are usually traditional investors such as banks, institutions, pension funds, etc. In their eyes, throwing $50 million into a startup fund is “risky” business compared to their other options, such as the stock market/real estate, which are lower cost, liquid and could “safely” return 7-8 percent per year. For them, 12 percent return on their money per year is good. Anything below that? Not worth the high risk they’re taking.

That brings us to…

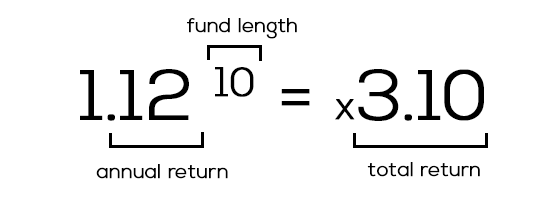

A 10-year fund needs to return 3x the fund size

We agreed VCs need to earn 12 percent return a year, right? Most funds, while only actively investing 3-5 years, are bound to 10 years. Many newer studies are showing that 12-14 year funds are more accurate for today, but let’s stick with 10 just to give the VCs a fighting chance. That annual 12 percent rapidly grows, showing the power of compounded interest. Let’s see the math:

Don’t forget Pareto: 80 percent of returns come from 20 percent of startups

Facts of life are that startups are hard. Breaking even is hard. Profits are hard. Keeping profits growing year over year (YoY) is even harder. Out of 10 companies, only two will really explode and IPO/M&A, giving our dear VCs some of their money back. The rest, as we’ll see, will fizzle out and die — or have a small liquidation event, which is pretty much the same.

Let’s start

So we have 10 startups and a fund that needs to return 3x within 10 years. Let’s assume it’s a $100 million fund, with $10 million invested in each company over the course of its life and a desired return of $300 million. To be fair, let’s also assume the VC jumped in on the A round, followed up on B and has 25 percent ownership at the end, with non-participating liquidation preferences.

Let’s look at a few different outcomes of our 10 startups after 10 years.

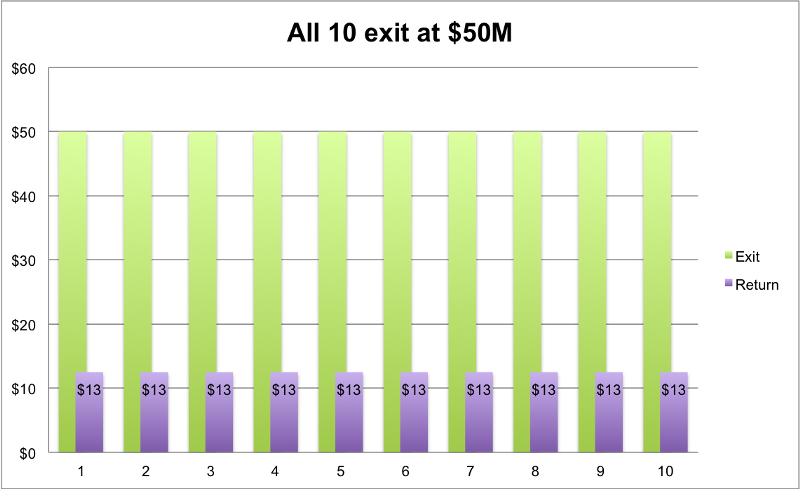

They all do “average” and exit at $50 million

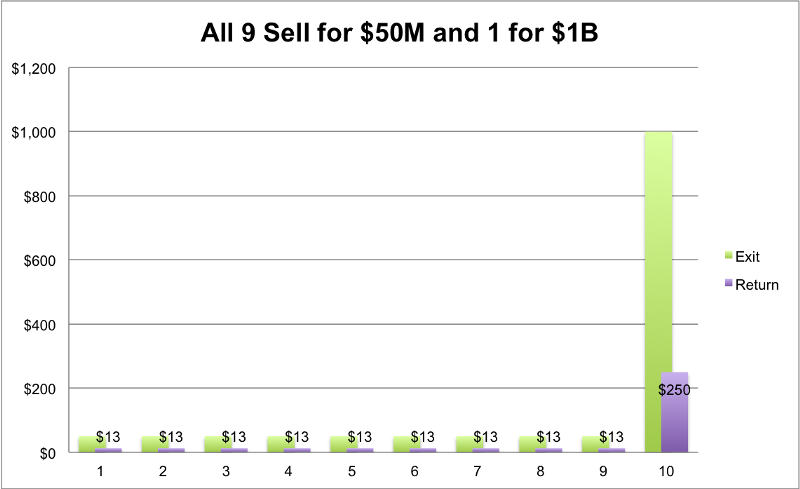

Green marks the exit size; purple the payout amount of the VC with his 25 percent.

Ten companies, they all exit at $50 million. The VC would return $12.5 million on each. Outcome: 10 * $12.5 million = $125 million. We needed $300 million, right? Not good. Let’s give them better odds.

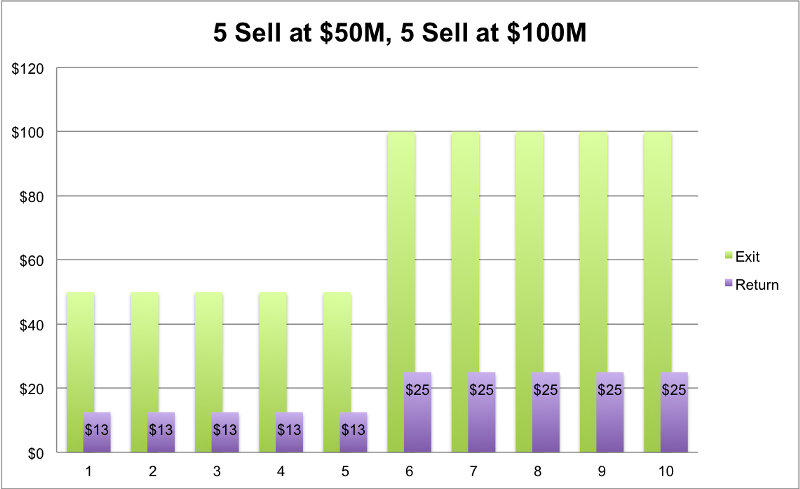

Half do average like before, and half do better

Five sold at $50 million, so $12.5 million return on each. The other five did much better and pulled off $100 million exits. The founders are overnight millionaires and their picture is in the paper. The VC? Not so much. Return: (5 * $12.5 million) + (5 * $25 million) = $187.5 million return. Still not quite at $300 million. No good.

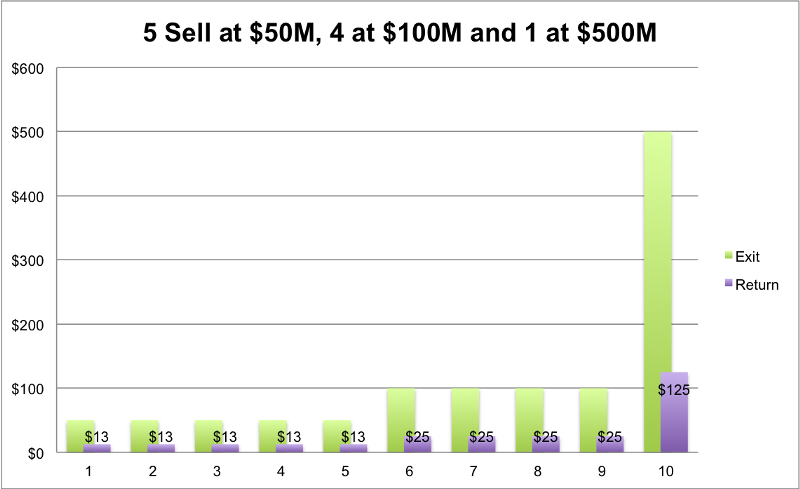

Majority do “average;” we’ll throw in an overachiever

So here let’s take our previous example, but make one of them a star. The 10th company, instead of selling for $100 million as before, now does $500 million. So our original five still sell at $50 million, four sell at $100 million and our new one at $500 million. Total returns for our VC: (5 * $12.5 million) + (4 * $25 million) + (1 * $125 million) = $287.5 million. We’re almost there! Just a bit more.

I think you see where this is going… we need one big fat unicorn exit!

We would need one large exit to see good profits. Something like this would work: nine startups sell for $50 million each and one goes for $1 billion: (9 * $12.5 million) + (1 * $250 million) = $362.5 million. We finally made it! Everyone is happy.

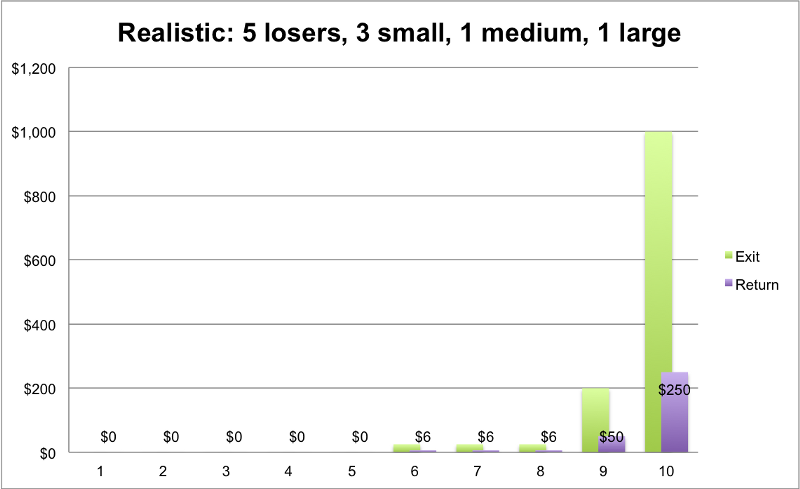

But is the last scenario actually feasible? Can you realistically expect all 10 companies to exit? Indeed, a 100% success rate sounds too good to be true. The more realistic scenario is that out of those 10, five will be complete losers, three will sell for small-medium amounts (which we just saw barely move the needle) but one or two will be big unicorn hugging exits ($1 billion-plus)

The realistic case

Five startups fail and do $0, three exit at $25 million, one exits at $200 million and our superstar does $1 billion. Let’s see the return on that one:

Return: (5 * $0) + (3 * $6 million) + (1 * $50 million) + (1 * $250 million) = $318 million

We’ve finally made it. Phew that was hard. Here we see some good returns, but is it actually realistic to think that the average fund can find this golden unicorn ticket? Probably not. The apparent truth is that most VCs aren’t doing as well as our “realistic case.” Only the good ones. Only the top 5 percent (not the top quartile!). And if the fund size is bigger, like the $1 billion funds we see being raised, then the math only gets harder, and the likelihood of a 3x+ return gets even lower.

But VCs always seem successful, right?

Yes and no. How are the rest of the 95 percent of VCs making ends meet? Not on their investing prowess, but rather on the fees that their investors pay. Most VCs are well (and primarily) compensated from the 2 percent annual fees on committed capital that they charge their investors ($100 million fund => $2 million/per year fees).

Even when they don’t generate great returns — and most don’t — their personal compensation is guaranteed from the fee stream. If that’s not enough, remember this: If one of their startups does see a liquidation event, they get 20 percent of the profits as a bonus. They’re sharing the upside, without any risk if things go south. As an entrepreneur, I wish I had that downside protection!

There’s still hope

It’s still hard for me to accept the fact that the only realistic way for a fund to get acceptable returns is to try to find only the companies that could be the next Ubers, Facebooks and Airbnbs. Under these rules, it doesn’t make sense for VCs to invest in anyone that can’t get to unicorn stage. There’s just no place for “average” companies looking to be worth and sell less than $500 million. At least not with VCs.

The way the numbers are worked out, it doesn’t look promising for any startup founder with less than shooting-to-the-moon goals. Even less so as a VC who’s fighting to keep his head above water and secure a follow-up fund. And don’t get me started on the LPs, who are the real losers here. They are the ones paying the fees, taking on the risk and then realizing disappointing returns at the end of the 10-year fund (which actually takes 15 years to liquidate).

But does it have to be like this? One place we can try to play around is our assumptions tab. Assumptions can and should be challenged:

-

- 10-year fund? Why not six? Reducing the fund length from 10 to six years decreases the expected return from the whopping 3x to a much more sustainable 2x. Much less pressure for a VC to return $200 million rather than 300. How can it be done in less time? One-two years for scouting and finding 10 A-round startups, four-five years for growth. Add some non-stop pressure on the founders to sell all the way around. The counter argument is that VCs are powerless to control exits — the founders run the show when it comes to exits (see Uber, Airbnb, etc.) — so gaining liquidity faster is unlikely.

- Screw traditional investors, move to the “cloud.” We should be able to find better access to capital that isn’t looking for 12 percent returns. Can’t we find investors willing to get an 8 percent stable yield in a $1 billion-plus fund diversified over hundreds of startups? Moving from 12 percent to 8 percent reduces the required return by a third. More lenient investment legislation (Jobs Act) is breeding more P2P and crowdfunding venture arms. Together with the 8 percent yield, you’ll find much more non-traditional investors joining the game. The counter-argument here could be you can find similar returns just by dumping some cash in the stock market and waiting it out. But then again, stocks don’t have the same “disruption excitement” as startups do.

- Invest in more startups/less cash in each. The assumption today is that VCs want to own 20-25 percent equity of any startup in which they invest, assuming they have cash to follow up. The reasoning being, if there actually is a realization event (exit/IPO), they want to score big. Instead of investing $10 million in each 10 startups, let’s try a more seed-level by investing $1 million in each of 50 startups. We’ll also throw a follow-up series A $3 million round for one-third of those, closing the $100 million round and giving the investor 10 percent equity in average. If half of those series A end up selling each for $100 million, we would see a return of (8 x $100 million x 0.15 percent = 120 million).

- Level the playing field. VCs and LPs aren’t aligned. The current industry standard for VC compensation is “2 percent and 20 percent.” Meaning VCs get paid 2 percent of the fund size in management fees (salaries) and an extra 20 percent of any liquidation event that might happen. So VCs get paid even when they “fail” to return adequate returns. LPs only get paid when VCs do an amazing job (rare). The end result is that both parties have separate agendas that don’t necessarily overlap. The ancient “2 percent and 20 percent” should be killed off and replaced with something that endorses higher alignment. Let the VCs fight for their supper.

- Only the strong survive. This may be hard for many VCs to read, but many of you out there should be killed off. Low-performing funds shouldn’t be able to raise additional rounds. This burden is on the shoulders of the LPs. They should take a cold hard look at the performance of their funds. Instead of looking just on the return rate (IRR), public market equivalent (PME) should be used to see how they performed compared with the market. For example, if a fund returned 13 percent IRR in 2014, but the public market actually did 14 percent, is that a sign of high performance? Nope. LPs need to smarten up and stop reinvesting in additional rounds seeing actual returns.

To summarize, venture capital is a tough business. LPs struggle to get paid in excess returns for the risk, fees and illiquidity they take on for investing in venture capital. Entrepreneurs struggle to scale and grow their companies and position for great exits. It’s not natural for a founder at stage one to know how he’ll grow from zero to billion. So many things will change along the journey. VCs struggle to generate the returns they promise, and only a very few manage to deliver.

But VCs enjoy the only downside protection in the business — they can rely on fees to pay themselves when their investments are mediocre. The long feedback cycle means that VCs can raise a few funds — and lock in a few fee streams — before their less than stellar returns catch up with them.

LPs and entrepreneurs don’t have that safety net. We live and die on our investment returns. We are the real risk takers in this business, not VCs.

Food for thought.

Sources:

- Venture Capital Funds – How the Math Works

- Does the Size of a VC Fund Matter?

- Cambridge — U.S. Venture Capital Index (2015 Edition)

- “We Have Met the Enemy…And He is Us”

Thanks to Gil Ben-Artzy for the insightful meeting/feedback that got me rolling with this article. Thanks to Diane Mulcahy, director of Private Equity at the Kauffman Foundation, for proofreading and feedback. Thanks to Liat Aaronson and Dr. Ayal Shenhav for the countless hours of VC lessons at the Zell Entrepreneurship Program that covered all the basics of this world. Finally, thanks to Jonathan Shieber of TechCrunch for helping facilitate this article.

If you like this article, subscribe to TechCrunch+

Use discount code TCPLUSROUNDUP to save 20% off a one- or two-year subscription

Comment